Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 is tied with No. 5 for being my favorite Mahler work. So naturally when a friend told me he was going to conduct it I was excited. No. 6 presents two problems that the conductor needs to resolve. One is the ordering of the middle movements. (Andante then Scherzo. End of story 🙂 ) The other concerns the hammer blows in the finale. Should there be two or three hammer blows?

Mahler composed his Symphony No. 6 during the summers of 1903 and 1904. He conducted the première at Essen on May 27, 1906. In the summer of 1906 he made many revisions. There is nothing remarkable about a composer making revisions after going through rehearsals. In fact, Mahler made revisions during the course of the rehearsals. He wrote to his wife Alma that the reason he was out of touch with her was that he was spending hours after rehearsal making revisions.

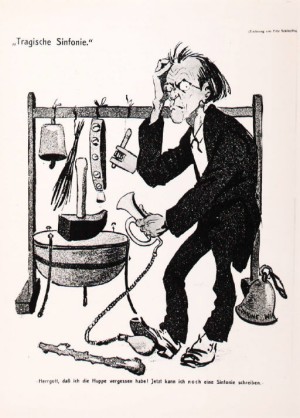

Alma’s memoirs relate that Mahler said that the Finale concerns a hero who “on whom fall three blows of fate, the last of which fells him as a tree is felled.” These three blows are played by a “hammer” that he described in a score footnote as being “short, mighty but dull in resonance, with a non-metalic character.” ( Kurzer, mächtig, aber dumpf hallender Schlag von nicht metallischem Charakter”) Alma wrote: “The notes of the bass drum . . . were not loud enough for him; so he had an enormous chest made and stretched with hide. It was to be beaten with clubs.” Alma leaves out the part of the story that the orchestra was making fun of Mahler as he was searching for the desired sound. At one point Mahler himself took a few whacks! (I wish Youtube existed back then! That’s a video I’d love to see) They did not use this contraption in the concert.

It has been suggested that Alexander Ritter’s poem, inspired by Strauss’ Tod und Verklärung (appended to the Strauss score), also influenced Mahler.

Now booms the final blow

By the iron hammer of death

Breaking in two the earthly body

Covering the eye with the night of death

Alma adds: “He anticipated his own life in music. On him too fell three blows of fate, and the last felled him.” All of this portrays Mahler as a prophet who foresaw that these three blows would represent three real-life misfortunes in his own life in 1907: Mahler’s 5 year old daughter Maria died, his tumultuous directorship of the Vienna Court Opera came to an end, and his not-yet-fatal heart disease was first diagnosed.

So what’s the problem?

At the Essen première, there were hammer blows at measures 336 (Rehearsal Number 129, p. 194 in the 1st ed.), 479 (RN 140, p. 216) and 783 (before RN 165, p. 260). He eliminated the third blow in his 1906 summer revisions. A terrific story for program annotations is that Mahler eliminated the third blow because he was superstitious enough to believe in his own prophetic powers and did not want to predict his own doom. Get rid of that last blow and you don’t die. In the following performances there were only two hammer blows.

Writing in the 1960s, Norman Del Mar stated that “Superstition must play no further part in what is now primarily an artistic decision.” This prompted some conductors – Mahler champion Leonard Bernstein included – to restore the third blow.

Was it superstition?

The fact is that the symphony was composed with zero hammer blows. The hammer blows were added to the autograph in blue pencil after it was completed.I Hans-Peter Jülg makes the case that there were five hammer blows in the manuscript. (the additional two blows at measures 9 and 530 were not explicitly marked “hammer”). Henry-Louis de La Grange makes the point that the existence of five hammer blows, well blows up the idea that the three that were heard in Essen were intended to be prophetic. Well, that’s that. Maybe. Hans Redlich in his 1968 edition claimed that Mahler decided to restore the third hammer blow in 1910. He presents no proof however.

What was going on in the music? The deleted hammer blows, at measures 9, 530, and 783, reinforced the “fate” rhythm and the major-to-minor triad. The two that Mahler left in did not. Apparently Mahler decided that he didn’t need to hit the listener over the head to make his point in those passages.

I’m just a composer who occasionally wears a musicologist suit for fun. My perspective is that musicologists would be out of a job if they didn’t have things like this to argue about. Let them have fun. So, 2 or 3? Mahler says 2.

But then Strauss, who conducted the Masonic Funeral Music K 477 to open the concert in which the symphony was premièred (was that a happy concert or what?) approached Mahler afterward and told him he couldn’t understand why the third hammer blow was not more prominent since it made such a good effect. Composers. Let them have fun too.

Sources

- Complete autograph dated May 1, 1905. Now in the archives of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna.

- The Copyist’s manuscript. Used by Mahler in the first Vienna reading a few weeks before Essen.

- The First Edition by C.F. Kahnt 1906 (Available online) The Dover reprint uses this edition. Three blows.

- The Second Edition by C.F. Kahnt 1907 (two)

- Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft Erwin Ratz 1963, 1998 (two)

Videos of “hammers” in practice

Suggested readings

Bekker, Paul. Gustav Mahlers Sinfonien. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1969.

Boulez, Pierre. “Gustav Mahler: Why Biography?” In Orientations: Collected Writings, Pierre Boulez,

292-294. Edited by Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Translated by Martin Cooper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Boulez, Pierre. “Mahler, Our Contemporary.” In Orientations: Collected Writings, Pierre Boulez 295-303.

de La Grange, Henry Louis. Gustav Mahler: Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion (1904-1907) (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999)

Del Mar, Norman. Mahler’s Sixth Symphony: A Study. London: Eulenberg Books, 1980.

Gartenberg, Egon. Mahler: The Man and his Music. New York: Schirmer Books, 1978.

Jülg, Hans-Peter. Mahlers Sechste Symphonie, 1986, pp 30 and 41.

Mahler, Alma, Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters, 3rd Edition ed. Donald Mitchell, trans. Basil Creighton, John Murray, London 1973, p.70

Mahler, Gustav. Symphonie Nr. 6. Ed. Erwin Ratz. Lindau: C.F. Kahnt, 1963.

Mattews, David. “The Sixth Symphony.” In The Mahler Companion,366-375. Edited by Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

2 Replies to “Mahler’s hammer blows”