Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg.

Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna.

Double Concerto in A Minor for Violin and Violoncello, Op. 102

Composed: the summer of 1887 near Thun, Switzerland.

First Performance: October 18, 1887 at Cologne in the Gürzenich Hall with Brahms conducting, Joseph Joachim and Robert Hausmann as soloists.

Instrumentation: Solo violin, solo cello, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 timpani, and strings.

Duration: ~33 min.

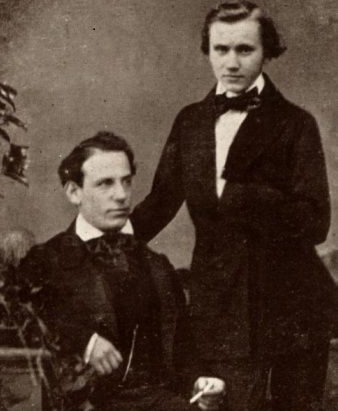

In April 1853, Brahms left his home city to tour with Hungarian violinist Reményi (Eduard Hoffmann) as accompanist. At the end of May, they arrived in Hanover where the already famous violinist, composer and conductor Joseph Joachim (1831–1907) had been recently appointed Kapellmeister at the King’s court. (his name is pronounced YO’ – ah – kim). Joachim’s successful London debut at the age of 12 had been with no less than Mendelssohn conducting Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Brahms first heard this concerto five years later in 1848 with Joachim as soloist. Reményi had studied violin alongside Joachim at the conservatory in Vienna and sought to renew contact and perhaps schedule a concert there. At Joachim’s request, the shy Brahms played for him several of his own compositions. Decades later, Joachim confessed to being “completely overwhelmed” by Brahms’ talent. The two soon became close friends and after Brahms parted ways with Reményi, Brahms stayed with Joachim who was by then attending courses at the university in Göttingen. In September of that year, armed with an introduction from Joachim, Brahms knocked on the Schumann’s door thus beginning his other important lifelong friendship.

In 1863 Joachim married alto Amalie Schneeweiss (yes, Snow White). Although Amelie gave up her opera career to be the mother of six children, she continued to sing. Brahms wrote songs for her including one for alto, piano and viola on the birth of their son who was named in Brahms’ honor. By 1883, Joachim had become increasingly suspicious of his talented and attractive wife. He accused her of having an affair with the publisher Fritz Simrock. Ever the gentleman, Brahms wrote a letter of consolation to her, defending her fidelity. Unfortunately, this letter was used as evidence in the divorce proceedings which Joachim initiated. Mostly due to this letter, the divorce was denied and the Joachims separated the following year. This caused a deep rift between the two old friends. Joachim would continue to play Brahms’ music, but refused to resume the friendship. Brahms continually tried to repair the relationship to no avail.

In August 1887, Brahms wrote to his publisher: “I must also tell you about my latest folly, a concerto for violin and cello! I had always intended to abandon the affair on account of my relations with Joachim, but to no avail. In artistic matters we have fortunately remained friends, but I should never have thought it possible for us to come together again on a purely personal level.”

For years, Robert Hausmann (1852–1909), the cellist of the Joachim quartet since 1879, had tried to get Brahms to write a ‘cello concerto for him. This double concerto that Brahms produced was unprecedented for the time.

While the idea of pairings of solo instruments against a larger body of strings was not new (i.e. Corelli and Handel’s Concerti Grossi, Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola K.V. 364, and Beethoven’s Triple Concerto Op. 56), Brahms was the first to unite the violin and the cello in this form. Brahms clearly intended something more personal. One can project the ‘cello part as representing Brahms himself, and the violin Joachim. Treating the soloists as opera characters was not an original idea, and Brahms made allusions in his letters that led some of his friends to believe that he was writing an opera. The unusual nature of a double concerto can be seen in a review by Brahms’s friend, Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, who wrote “Such a double concerto is like a drama with two heroes instead of one, two heroes who, laying claim to our equal sympathy and admiration, merely get in each other’s way.” Needless to say, Brahms was far too skilled in this, his last orchestral work, to let the two heroes get in each other’s way.

On September 21 and 22, Brahms met with Joachim and Hausmann for rehearsals in Baden-Baden using Clara Schumann’s piano. This reinforces the idea that the concerto is chamber music for soloists and orchestra, as if his C minor Piano Trio Op. 101 from the previous year were a foreshadow. The following day, the Kursaal orchestra there gave a reading of the score in a private performance in the Louis-Quinze Room of the Kurhaus before it was formally premiered in Cologne with Brahms conducting. In their collaboration on the Violin Concerto, Joachim simplified the violin part. In this concerto, he went in the other direction, making it much more difficult.

There are three movements.

I. Allegro (A minor)

II. Andante (D major)

III. Vivace non troppo (A minor—A major)

The first movement begins with a bold statement by the full orchestra, but after only 4 measures the solo ‘cello takes over, launching into a cadenza. The brief initial orchestral outburst is full of portent, for much of the following material is spun from it. This main theme is in two parts; one a repeated figure in duple meter and another based on triplets, thus introducing a conflict – 2 vs. 3 – from the outset. The ‘cello is interrupted by the winds gently introducing fragments of what will become the second theme. They are in turn interrupted by the solo violin which is soon joined by the solo ‘cello. The shape of the motif first played by the violin references Joachim’s personal F-A-E (Frei aber Einsam) motto (to which Brahms had previously responded in the opening three notes of his Third Symphony in 1883, F-A-F “Frei aber Frölich” – “free but happy!”). An upwardly rushing passage leads back to an orchestral tutti where we hear with a more complete statement of the first theme. This is followed by a syncopated figure which will be prominent in the development. The second theme is then fully presented by the orchestra.

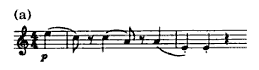

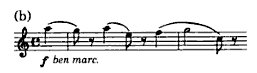

The second theme is a nod to the first theme in first movement of Viotti’s (1755-1824) Violin Concerto No. 22, which was a favorite of Brahms and Joachim. As you can see from the example, Brahms’ theme (marked b) is more of an allusion to Viotti’s theme (marked a) than a direct quotation; a wink between two knowing friends.

Following an initial horn call, the andante D major second movement’s main theme is a lovely rising and falling arch played by the soloists in octaves accompanied by the strings. There is a hymn-like middle section followed by a return of the main theme, but this time with a pizzicato accompaniment. The hymn returns in the tonic key leading to an extraordinarily beautiful coda to bring the movement to a gentle close.

In the A minor rondo third movement, Brahms’ interest in Hungarian folk music, which was the initial basis of his friendship with Reményi, shines through. The Gypsy flavor is evident as well as humorous interruptions of the ‘cello by the violin. In fact, Brahms wrote his Zigeunerlieder (Gypsy Songs) the same summer at Thun as when he wrote this concerto. The finale begins with the rondo (recurring) theme played softly by the ‘cello first then the violin. There are two contrasting episodes, the first a broad C major passage first presented by the ‘cello then quickly followed by the violin with both soloists playing double stops (each playing two notes at once, the second a dramatic rhythmically punctuated theme also presented with double stops from the solo instruments. The demands on the soloists are limited only by the technical possibilities of their instruments, as Brahms explores fully the tonal colors, sonic depths and beauty of these instruments individually and collectively with the orchestra, moving the listener through different musical scenes and feelings as though we are listening through a musical kaleidoscope. The coda begins quietly in a slower tempo, but soon the the original exuberance returns for a triumphal conclusion in A major.

Resources

Public domain score

Manuscript with Brahms’ annotations. Select the concerto from the menu.

Spotify playlist of the concerto. You can join Spotify for free.

Rattle Playlist on YouTube.

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00000I7VO][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000NA1X8U][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0001WGDXA][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000000S9R]

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=3795765641][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0757913652]

One Reply to “Brahms : Double Concerto”