Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Don Juan

Composed May–September 30, 1888

First Performance: November 11, 1889, in Weimar, conducted by the composer.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, glockenspiel, harp, and strings

Background

Strauss made his first sketches for Don Juan in the fall of 1887, and completed the score in the summer of 1888, two years after the completion of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony. This first masterpiece, which propelled him to fame, was completed when Strauss was only 24! At such an age the virtuosity displayed is astonishing, but perhaps Michael Kennedy is correct that this is “tumescent, erotic music, redolent of the passion of a man in his mid-twenties.” (yikes!) Much later, Strauss in a rehearsal of the piece advised the players that “all would go well if they imagined they were engaged rather than married.”[1]

Strauss received his early musical training from his father who was a professional horn player. Influenced by his father’s anti-Liszt/Wagner stance, Strauss’ early works were not programmatic. In 1885 he left Munich to accept a position at Meiningen as assistant to Hans von Bülow. There he was introduced to Liszt’s ideas of Zukunftsmusik (Music of the future) by Meiningen violinist, Alexander Ritter (who was married to Wagner’s niece). Strauss embraced the idea that the “poetic idea” should guide the development of the music. His first efforts in this direction were the symphonic fantasy [amazon text=Aus Italien&asin=B0000013PA] followed by [amazon text=Macbeth&asin=B002AT46H2] (1886), neither of which were entirely successful. However, beginning in 1888, Strauss created a series of Tone Poems (he preferred this term – Tondichtung – over Symphonic poem) destined to be masterpieces: [amazon text=Don Juan&asin=B0000025JH] (1888), Tod Und Verklarung ([amazon text=Death And Transfiguration&asin=B0000025JH]) (1888-89), [amazon text=Til Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks&asin=B0000025JH] (1894-95), [amazon text=Also sprach Zarathustra&asin=B000004198] (1895-96), [amazon text=Don Quixote&asin=B00000262R] (1896-97), and finally culminating in [amazon text=Ein Heldenleben&asin=B000004198] (A Hero’s Life) (1897-98). Although Strauss wrote several orchestral works after Ein Heldenleben, he turned most of his attention to the Lied and Opera in his later life.

Nikolaus Lenau, the pseudonym of Nikolaus Franz Niembsch von Strehlenau (1802-1850), was one of Austria’s greatest lyrical poets. In 1844, he began writing Don Juan, a verse drama, only a fragment of which was published posthumously. Lenau’s poem was Strauss’ inspiration for his own composition Don Juan. Key to understanding this work is that Strauss was drawn to Lenau’s psychological treatment of his famous subject. Strauss vividly portrays the Don’s mental deterioration throughout the work. The form Strauss chose to use is that of a Sonata first movement with two development sections.

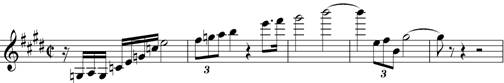

The exhilarating opening grabs the listener’s attention and doesn’t let go until the final moments of the piece. These first few measures contain several ideas that are developed throughout.

The principal theme of the first section is derived from the motifs in the introduction.

This theme is developed in a self contained section representing the Don’s first “adventures.” This is followed by a lyrical melody which marks his first love scene.

A second love scene occupies much of the middle of the work. The hauntingly lovely melody brings the oboe to center stage over a static sustained background.

After building in intensity, this section culminates with this theme modified with motives from the opening, announced heroically in the horns over a high string pedal point.

This love scene is followed by a second development section which is known as the Carnival scene. Don Juan’s downfall starts here when he finds a statue of a nobleman he killed and invites him to dinner. The statue does not come to dinner but rather his son Don Pedro.

The final section depicts a duel between Don Juan and Don Pedro. Themes are recapitulated and the tempo gradually presses forward (stringendo) to a climax on a B dominant seventh chord repeated fortissimo in triplets. Realizing that his assured victory against Don Pedro would bring him only more of the life with which he has become bored, Don Juan drops his sword to allow Don Pedro to provide the final thrust of the match. At that instant, there is a sudden pause in the music. The transition from this exciting swashbuckling to the moment when Don Juan throws away his sword to receive the death blow from Don Pedro is marked by a very soft sustained A minor chord. The moment of the death blow is marked by the trumpets dissonant F natural over this serene A minor.

The work ends dramatically with Don Juan’s life ebbing away. His collapse to the ground and loss of strength is portrayed by descending thirds rustling in the violins, with swelling and diminishing tremolos in the strings until he reaches his last breath. With a final ascending scale in the first violins, his spirit departs to the heavens. All that is left is desolation, and the nerve-induced final shudder of his body depicted in the violas. Two unison pizzicati on E announce the Don’s demise.

Strauss suggested that the excerpts from Lenau’s poem quoted in the score be printed in program notes. These verses, spoken by Don Juan,are from the opening and closing of the drama.

Fain would I run the magic circle,

Immeasurably wide, of a beautiful woman’s manifold charms,

In full tempest of enjoyment,

To die of a kiss at the mouth of the last one.

O my friend, would that I could fly through every place

Where beauty blossoms, fall on my knees before each one,

And, were it but for a moment, conquer.

*

I shun satiety and the exhaustion of pleasure;

I keep myself fresh in the service of beauty;

And in offending the individual I rave for my devotion to her kind.

The breath of a woman that is as the odor of spring today

May perhaps tomorrow oppress me like the air of a dungeon.

When, in my changes, I travel with my love In the wide circle of beautiful women

My love is a different thing for each one;

I build no temple out of ruins.

Indeed, passion is always and only the new passion;

It cannot be carried from this one to that;

It must die here and spring anew there;

And, when it knows itself, then it knows nothing of repentance.

As each beauty stands alone in the world,

So stands the love which it prefers.

Forth and away, then, to triumphs ever new,

So long as youth’s fiery pulses race!

*

It was a beautiful storm that urged me on;

It has spent its rage, and silence now remains.

A trance is upon every wish, every hope.

Perhaps a thunderbolt from the heights which I contemned,

Struck fatally at my power of love,

And suddenly my world became a desert and darkened.

And perhaps not; the fuel is all consumed

And the hearth is cold and dark.[2]

[1] Michael Kennedy, “Richard Strauss. The Master Musicians”

[2] Norman Del Mar, Richard Strauss: A Critical Commentary on His Life and Works

Resources

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0000013PA][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B002AT46H2][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0000025JH][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000004198]

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=0486237540][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0486419096][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0000D3TZN][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0140D1X8K]

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=080149317X][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0801493188][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0801493196]

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=0460031481][amazon template=iframe image&asin=2213609764][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0521027748]