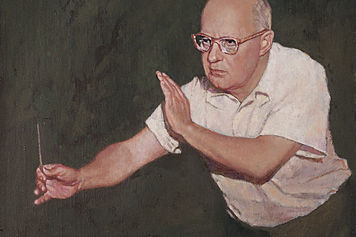

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963)

Born November 16, 1895, Hanau (near Frankfurt)

Died December 28, 1963, Frankfurt.

Symphonie Mathis der Maler

Composed 1933-1935

First Performance: March 12, 1934 in Berlin conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (second doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (second doubling English Horn), 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets in C, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, 5 percussion (Triangle, Tambourine, Tamburo/Tamburo piccolo, Cymbals, Bass Drum/Tam Tam), harp and strings

Paul Hindemith was born in Hanau near Frankfurt.. He studied violin and composition at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt eventually becoming first violin of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. After the First World War he returned to Frankfurt, playing the viola in the Amar Quartet from 1921 to 1929. He continued performing throughout the twenties and in 1929, he gave the first performance of William Walton’s [amazon text=Viola Concerto&asin=B000001487].

His first reputation as a composer emerged after the premiere of his String Quartet in 1921 at the Donaueschinger Musiktage, a festival which he helped found. His compositional activities centered on music that could be performed with minimal forces leading to a series of works simply entitled [amazon text=Kammermusic&asin=B00008MLTZ] (Chamber Music) I, II and so forth. Indeed throughout his career he produced many examples of what has been termed Gebrauchsmusik (a term disliked by Hindemith) including writing a sonata for each instrument, stopping just short of a sonata for bagpipes.

In 1927 Hindemith was appointed professor of composition at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin. He started to produce practical training materials for his students as well as theoretical works which solidified his own compositional thinking.

His Unterweisung im Tonsatz ([amazon text=The Craft of Musical Composition&asin=0901938300]) presents his theories that were based on the overtone or harmonic series. He derives two series which show degrees of harmonic and melodic tension. One noticeable result from this is in his harmonic and melodic writing based on fourth and fifths. He never abandoned tonality which he described as a natural force like gravity. The major triad which appears in the overtone series appears frequently, most often as a first and last chord of a work. In fact his only mature work that does not end with a major chord is his [amazon text=Requiem&asin=B000003CTZ]. His concept of tonality centers on pitches rather than being based on traditional major or minor modes. For example his [amazon text=Symphony in Eb&asin=B000000APF] centers on Eb rather than being in Eb major or Eb minor.

In 1930 his mature style emerged with the [amazon text=Konzertmusik for Strings and Brass, Op. 50&asin=B000000AZ5] (he stopped assigning opus numbers after this) which also represented a turn to larger symphonic forces.

Hindemith composed the symphony at the request of conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler for the Berlin Philharmonic’s 1933-34 concert season. At the suggestion of his publisher, Hindemith had begun work on the opera [amazon text=Mathis der Maler&asin=B000LQEHEI] (Matthias the Painter) in 1933. In order to not be distracted from the opera he decided to use its materials as the basis of the symphony. He had planned to divide the work into four preludes and interludes each depicting a panel from the Isenheim altarpiece.

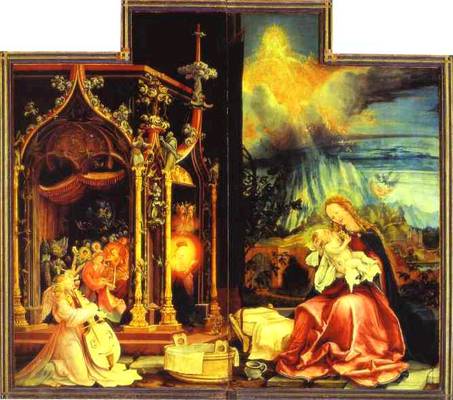

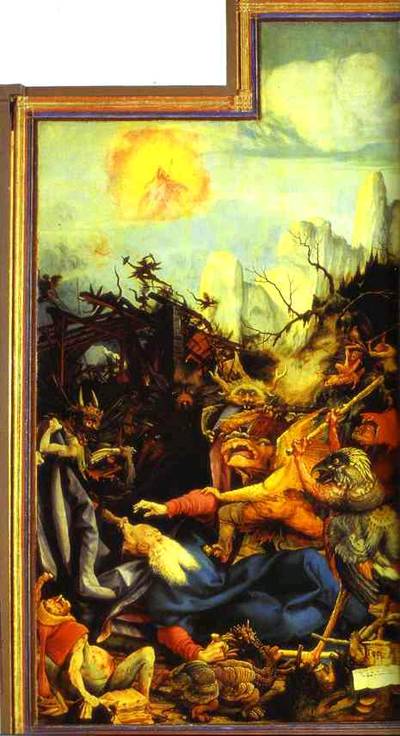

The Isenheim Altarpiece was painted between 1505 and 1516 by Mathis Gothard Nithart (?-1528) (named Matthias Grünewald by his first biographer) for the Antoniterkloster in Isenheim. Today it is at the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar (Alsace-Lorraine).

Mathis was faced with the turmoil of the Peasants’ War of 1524-1525. He pondered the function of the artist in society. Is what the artist creates enough or should he become involved in politics? The opening aria of the opera, “Is was du schaffst und bildest genug?”, presents this central question. In Hindemith’s libretto Mathis gives up painting to join the peasants. After being disappointed by the peasants he realizes that he has betrayed his art. In a vision art is restored to him.

The first movement was completed in November 1933 and the second in February 1934. But since he not finished with the libretto the third movement was not started until a few weeks before the premiere in March 1934. He had the inspiration to combine two panels representing The temptation of St. Anthony with The meeting of St Antony with St Paul the Hermit for the climax of the opera.

In Hindemith’s program notes for the opera premiere he describes the music as being “…not altogether free invention: old folksongs, songs of invective from the time of the Reformation and Gregorian chant provide fertile ground for the music of Mathis…”

The symphony’s premiere in Berlin was a great success which received a 20 minute standing ovation. Only a month later another conductor was forbidden to perform it. Hindemith and Furtwängler has found themselves on the wrong side of the Nazis. Later in 1934 Furtwängler published an essay entitled “The Hindemith Case” in defense of the composer. Unfortunately this got him fired from all of his posts.

Hindemith was never a favorite of the Nazis. In fact he had offended party officials with an earlier opera in which a soprano sang an aria from a bathtub. In April 1933 half his music was banned as “cultural Bolshevism”. The success of Mathis led Goebbels to denounce Hindemith as an “atonal[sic] noise-maker.”

In October 1936 all of his music was banned and was dismissed from his Berlin teaching post the following year.

Since the ban was still in effect the world premiere of the Mathis der Maler opera could not take place in Germany. Instead Robert Denzler conducted the premiere on May 28, 1938 at the Stadttheater in Zürich.

Four month after being prominently featured in a Nazi exhibition entitled “Degenerate Art” he began his exile in September 1938 by moving to Switzerland. Hindemith left Switzerland on February 4, 1940 to live in the United States where he was offered a teaching post at Yale. He became an American citizen on January 11, 1946. In September 1953 he moved to Blonay Switzerland where he remained for the rest of his life.

Towards the end of his life his music was considered old fashioned. He was described at Darmstadt –a new music center- as “old iron.” He responded that “It is an honor to belong with the “old iron”. Music history is full of old iron, and it was always more durable than new bullshit.”

The conventional thinking has been that Hindemith’s libretto – which even includes a book burning scene – was a reaction against the Nazis. In fact Hindemith considered Hitler’s regime as a passing nuisance much as we would endure a Clinton or Bush administration knowing that their nonsense would soon be over – even in the face of his brother-in-law being sent to a concentration camp (his wife was half-Jewish) and several of his colleagues being banned. Some writers have speculated that Mathis with its “German Theme” was Hindemith’s attempt at rehabilitation.

I. Engelkonzert

The first movement, entitled Engelkonzert (Concert of Angels), corresponds to the panel which depicts Mary holding the infant Jesus while being serenaded by three angels. This movement appears twice in the opera. It serves unaltered as the opera’s prelude and later appears when Mathis has a vision of this painting.

The Concert of angels begins with three softly shimmering G major chords. The folk song Es sungen drei Engel ein süssen Gesang (Three angels were singing a sweet song) written around 1605 (the text dates back to 1278) is introduced on Db (the furthest distance from G in his theories) by the trombones, then taken over by the horns playing it up the interval of a third (now on F) and finally reaching a sparkling climax with the woodwinds, glockenspiel and trumpets up yet another third (on A). The number three figures prominently in this movement much like Bach writing a triple fugue (St. Anne) in Eb (3 flats) to symbolize the trinity. This music returns in the first scene of the opera’s sixth tableau in which Mathis and Regina the daughter of the peasant leader are in flight. Mathis describes each angel while Regina sings the folk song.

Example 1. Es sungen drei Engel ein süssen Gesang

There are themes for each of the three angels. The first “fairly lively” theme is centered on G. At the end of the first statement it begins to be fragmented separated by three chords.

Example 2. First angel

After a three chord cadence on G the first theme dissolves in the woodwinds towards F# as the second theme is quietly introduced by the strings.

Example 3. Second angel

The woodwinds and strings play the second theme which leads back to G after several statements.

Example 4. Third angel

The third theme is presented by the flutes over the strings which play a lively ostinato on G and D. The violins then pick up a bit of the theme leading into “the three chords” which snippets of the first theme reappear in the lower strings to a cadence on a B major chord played three times signaling the end of the exposition.

The development combines and develops the three angel themes leading to a sparkling climax of the movement which contrapuntally combines the three themes with the Drei Engel folk song which is once again presented by the trombones on Db.

The climax dies away to a reintroduction of the third theme once again over the same ostinato but up a major third. The first theme reappears over the ostinato followed by the second theme.

The movement closes with a final fortissimo statement of the first theme by the strings and winds back in G followed by the brass ending the movement with three powerful chords.

II. Grablegung – Entombment

The second movement is based on the panel in which Christ is laid in the tomb. In the opera it is first heard as the interlude between the scenes of the seventh and final tableau in which the daughter (Regina) of the peasant’s leader dies, and again at the conclusion of the opera when Mathis bids his farewell.

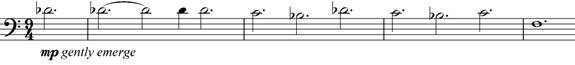

The strings begin by softly introducing a halting ascending then descending theme.

Example 5.

The flutes introduce a quiet desolate theme with is then taken up by the oboe, back to the flutes and then again to the oboes before the halting opening material returns played by the full winds forte. A brief coda featuring clarinet and flute solos bring the movement to a quiet close.

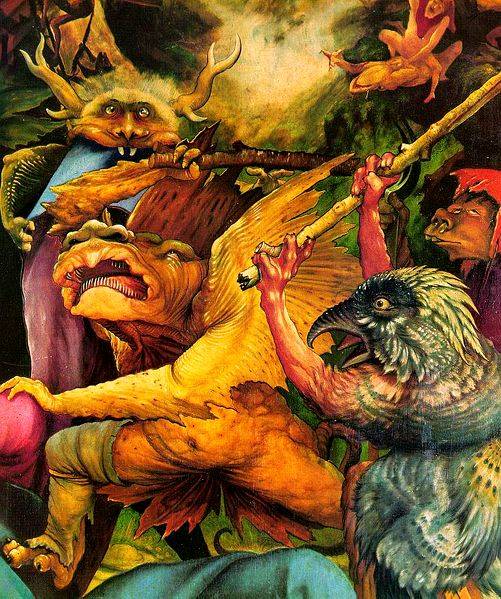

III. Versuchung des Heiligen Antonius (The temptation of St. Anthony)

The Temptation of St. Antony begins with the unison string declaiming long rubato melismatic passages punctuated by a short two note cadence. This material is the introduction to the opera’s Sixth tableau. In this tableau the Mathis becomes St. Antony and the opera’s main characters bring the tormentors from Mathis’ painting to life.

After the opening recitative a triple meter gallop is launched with the strings playing a chromatically twisted melody.

Example 6. Primary theme

In the second scene of the sixth tableau the full chorus sings this theme taunting Mathis with the words Dein ärgster Feind sitzt in dir selbst. (Your worst enemy is inside yourself).

After a brief silence to underscore its importance a descending motif is sung fortissimo by the full chorus to the words Wir plaugen dir (We torment you).

Example 7. Wir plaugen dir (We torment you)

A Latin inscription from the altarpiece “Where were you, good Jesus, where were you? Why have you not come to heal my wounds?” is printed in the score on the movement’s first page and is sung by Mathis at the height of his torments.

After a brief quieter and slower respite the movement builds momentum again developing the Wir plaugen dir motif while the woodwinds intone the Gregorian chant Lauda Sion Salvatorem (Praise Zion to the Savior) over an ostinato played by the horns.

Example 8. Chant

Example 9. Ostinato

The climax of the sixth tableau is when St. Paul admonishes Mathis to “Geh hin und bilde” (Go forth and create).

The sixth tableau ends with an alleluia sung by Sts. Antony and Paul. In the symphony the alleluia is presented by the brass choir to bring the symphony to a powerful conclusion.

Example 10. Alleluia

Resources

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000001487][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00008MLTZ][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0901938300][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0000U1NHE][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000000AZ5][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000003CTZ][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000000APF][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000LQEHEI][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000002RUM]

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=3795761735][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00Y34MBP6][amazon template=iframe image&asin=3874842193]