Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Born March 9, 1910 in West Chester, PA.

Died January 23, 1981 in New York City.

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 14

Composed 1939 and 1940 in Switzerland and Paris.

First Performance: February 7, 1941 with Albert Spalding as soloist Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 French horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, tamburo militaire, piano, strings.

Samuel Barber was a prodigy who was surrounded by music as a youth. His aunt was Metropolitan opera contralto Louise Homer.

He entered the newly opened Curtis Institute in Philadelphia at the age of 14 as one of its first students. He studied piano, voice and composition there.

Barber’s biography shares a few events with that of Berlioz. Barber won the (American) Prix de Rome for which he wrote the Symphony in One Movement in Rome. Much later his opera Antony and Cleopatra opened the new Metropolitan Opera house in 1966. Unfortunately it came close to being his own Actium due to circumstances beyond his control as was the case with Benvenuto Cellini.

His most famous work – and for a while the best selling classical work on iTunes – is the second movement from his String Quartet which he rearranged as the Adagio for Strings. Toscanini –never one to pay the least attention to American composers- premiered the work in 1938 with the NBC Orchestra which gained national exposure for the young composer.

The Violin Concerto was commissioned by a Philadelphia businessman for one of his young violin protégés. Barber travelled to Switzerland and completed the first two movements. The following year he completed the final movement in Paris. There are conflicting stories as to the reception of the work by the businessman and violinist. One story is that the violinist didn’t like the lack of virtuosic display in the first two movements. So Barber promised a flashy finale. The violinist then allegedly stated that the finale was unplayable (unlikely considering his undisputed talent). In another story, the violinist asked that the finale be expanded. And in yet another account, he objected to the character of the finale being so different from the other movements. In any case the work was rejected – on the grounds that the work was unplayable, the businessman allegedly asked for his money back! In 1996 an attorney for the violinist threatened legal action against anyone propagating “defamatory” remarks (i.e. Barber’s account of the story) against the violinist.

The work was first performed to a small invited audience at the Curtis Institute by student violinist Herbert Baumel who proved that the work was indeed playable after a preparation of only a few hours. The official premiere was given by Albert Spalding (1888-1953) on February 4, 1941, with Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The three movements are

I Allegro

II Andante

III Presto in moto perpetuo

Unlike many concerti there is no introduction. Instead we are immediately drawn into the piece by the soloist playing the lyrical first theme over a quiet accompaniment.

Example 1. Soloist’s opening theme

In Barber’s notes for the premiere he writes that “This movement as a whole has perhaps more the character of a sonata than concerto form.”

The clarinet introduces a contrasting second theme which is then answered by the soloist.

Example 2. Second theme (Clarinet)

The strings reprise the opening theme. The soloist answers with a new more animated theme.

Example 3. Third theme (Soloist)

There is a brief climax. The second theme returns as a series of woodwind solos over a pedal point (a repeated low pitched note).

Another climax builds when the trumpets play the second theme while the soloist plays an obbligato leading to the first theme played forte by the full string section.

The music settles down and the soloist returns with the first theme followed by a short cadenza. The woodwinds respond with the second theme which leads to the full strings playing the first theme again. The soloist answers with the third theme leading into another more extended cadenza. The pedal point returns. Over this the oboe and then the soloist plays the second theme.

The movement ends quietly with a few brief woodwind solos playing snippets of the first theme.

For the second movement Barber offers this succinct description. “The second movement — andante sostenuto — is introduced by an extended oboe solo. The violin enters with a contrasting and rhapsodic theme, after which it repeats the oboe melody of the beginning.”

One is reminded of a similar opening in the Brahms Violin Concerto to which Sarasate famously declared, “do you think I could fall so low as to stand, violin in hand, and listen to the oboe play the only proper tune in the work?”

Example 4. Second Movement Oboe solo

The oboe solo is then taken up by the ‘celli and then the clarinet. The full string section then plays this theme.

A brief quiet Horn solo introduces the violin soloist who enters playing a slow build-up in quarter notes until the rhapsodic second theme is played.

In the middle of the movement there is a sort of cadenza where the soloist is accompanied by sustained notes in the bassoon and horn.

Finally the solo violin plays the oboe solo in its low register.

The full string section picks up this theme which is now in the stratosphere. The soloist answers in same register as beginning oboe. The soloist plays a very brief cadenza and the work comes to a quiet conclusion.

Barber wrote that “The last movement, a perpetuum mobile, exploits the more brilliant and virtuosic character of the violin.”

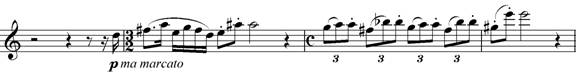

The soloist begins played a series of triplets with daemonic if not demonic “perpetual motion” intensity that does not relent throughout the entire movement.

There are only fleeting contrasts to these insistent triplets. The texture is frequently punctuated by brief syncopated chords and the flutes, piccolo, oboe and clarinet introduce a brief snippet.

Example 6. flute piccolo oboe clarinet

This finale is indeed utterly different in character from the first two movements. The gentle lyricism of the opening movements is replaced by a new more modern idiom to such an extent that many writers have pointed to this as a turning point in Barber’s compositional work.

Resources

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000GUJZSC][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00000IYO9][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0000030D8]

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00IIBB732][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0793555620][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0793554586]

Dear Mr. De Lisa:

I want to draw your attention to the website isobriselli.com where you can find the definitive information on the Barber violin concerto. Your program notes are based on outdated and inaccurate information and need to be corrected. As the notes stand, they demean the reputations of both Mr. Fels, who commissioned the work, and Iso Briselli, for whom the work was written. Thank you for your attention to this matter of considerable importance to the Briselli family.

Marc Mostovoy

I “demean the reputations” of no one in these notes.

1) No names are given.

2) I’d be negligent if I did not mention the controversy.

3) I make no conclusions in the matter.

Perhaps you missed this sentence: “There are conflicting stories as to the reception of the work by the businessman and violinist.” I then presented the conflicting stories.