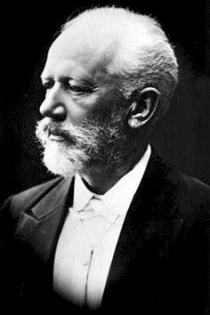

Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Born May 7, 1840 in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia.

Died November 6, 1893 in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, Op. 74 Pathétique

Composed February 16 to August 31, 1893.

First Performance: October 28, 1893 in the Hall of Nobles, St. Petersburg with the composer conducting the Russian Musical Society Orchestra.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.

Amid a cholera outbreak in St. Petersburg, Tchaikovsky drank a glass of unboiled tap water – in spite of warnings from the staff and his friends during a post theater dinner at Leiner’s restaurant on November 1. Tchaikovsky thus committed suicide by poisoning himself because he was uneasy about his homosexuality and unrequited love for his nephew Vladimir “Bob” Davidov, to whom he dedicated his Pathétique symphony. After all, homosexuality had been illegal in Russia since 1832. Punishment included deportation and whipping, and at the least, public humiliation and loss of social standing.

Or, Tchaikovsky was driven to suicide when Tsar Alexander III declared that “Tchaikovsky must disappear at once,” after the caretaker at Tchaikovsky’s apartment building reported that the composer had seduced his son. Or maybe as Tchaikovsky’s sister-in-law Olga Tchaikovskaya claimed, he was poisoned by one of his doctors, Vassily Bertenson, under orders from the Tsar.

Or, Tchaikovsky cruised parks and dives, hired professionals, and predictably lost that lottery.

Or, Tchaikovsky drank that tap water because he was distraught when his patroness Nadezhda von Meck cut off her financial assistance to him, cursing her on his deathbed.

The most recently popular myth was Soviet musicologist Alexandra Orlova‘s story which was even published in the 1980 edition of the New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (but deprecated in the current edition). Tchaikovsky had the misfortune of becoming involved with the 18 year old nephew of Duke (or Count) Stenbock-Fermor. The furious Duke wrote a letter of condemnation to his friend the Tsar. He asked Nikolai Jakobi who was chief prosecutor of the senate to deliver the message. Jakobi read the letter but did not deliver it. He had been a classmate of Tchaikovsky’s at the St Petersburg School of Jurisprudence. He organized a “court of honor” of seven fellow classmates – now all famous lawyers or politicians – who passed judgment on Tchaikovsky. They promised to destroy the letter only if he committed suicide in order to avoid tarnishing the reputation of the school. The method was to take small doses of arsenic to make it appear to be cholera which had similar symptoms.

Tchaikovsky drank Chablis at Leiner’s restaurant and was actually feeling unwell before eating anything. He was distressed that his patroness cut off correspondence but did not curse her on his deathbed. He actually was a cruiser in his youth but once he became well known as a composer he stopped these activities.

Homosexuality was not uncommon in 19th centur Russia. Indeed, the School of Jurisprudence was regarded as a hotbed of this activity and many of the Tsar’s groupies were known to be gay. It is quite possible that the Tsar would have just ignored the “scandal” and not subject him to the same fate Oscar Wilde suffered a few years later.

Orlova’s myth and the others have been effectively refuted in Alexander Poznansky’s book Tchaikovsky’s Last Days. Death from cholera was the official version endorsed by doctors but there is no final word on the actual cause of death – bad luck or suicide.

On February 11, 1893 he wrote to his nephew Bob “I had an idea for another symphony – a program work this time, but its program will remain a mystery to everyone – let them guess. But the symphony will be called “Program Symphony” (no. 6).” Tchaikovsky never disclosed what the program was. During the intermission of the first performance, Rimsky-Korsakov asked for details on the program but Tchaikovsky refused. It is possible that Tchaikovsky developed this symphony from an earlier discarded “Life” symphony in E flat. Perhaps he had the program for the discarded symphony in mind for the sixth: “The underlying essence… of the symphony is Life. First part – all impulsive passion, confidence, thirst for activity. Must be short the Finale death – result of collapse. Second part love: third disappointments; fourth ends dying away”

Modest asserted that he suggested the subtitle “Pathétique” meaning “passionate” or “emotional” instead of “Program” the day after the premiere but Tchaikovsky had already used the equivalent Russian word in a letter to his publisher in September.

Tchaikovsky conducted the first public performance of the Sixth Symphony on October 28, 1893 in Saint Petersburg, at the first symphony concert of the Russian Musical Society. It was a moderate success. After the performance, Tchaikovsky wrote “Something odd happened with this symphony! It’s not that it displeased, but it produced some bewilderment. As far as I myself am concerned—then I am more proud of it than any of my other works.” Nine days after he conducted the premiere he was dead. Subsequent performances of his “Suicide” symphony were resounding successes.

There are four movements:

1. Adagio—Allegro non troppo (B minor).

2. Allegro con grazia (D major).

3. Allegro molto vivace (G major).

4. Finale. Adagio lamentoso (B major).

The symphony very quietly and slowly opens in the dark and brooding nether region of the bassoons. This introduction foreshadows the first theme which is presented by the violas at the beginning of the Allegro non troppo section. The first theme builds to a climax to prepare us for the second theme.

Example 1. First movement first theme

In most symphonies the second theme is overshadowed by the first, but not in this one. This soaring passionate theme is justly one of his most famous.

Example 2. The big tune

We then hear a fugue like development section which can be described as a “free fantasia” where the first theme is broken up and the second is elongated. We also hear the trombones solemnly intone the B minor Russian death chant which is a quotation from the traditional Russian Orthodox Requiem Mass, sung to the words “with thy saints, O Christ, give peace to the soul of thy servant.” Robert Craft relates a story where he played this movement in the room next to a sick Stravinsky whereupon his wife came rushing in scolding him to turn it off due to its connotation. The recapitulation begins with the first subject, which is now loud and assertive. The second theme returns marked “con dolcezza” but is accompanied by agitated strings. The coda feature pizzicato strings playing a “walking” accompaniment while the winds play a sustained chorale to close the movement.

The second movement is in Ternary Form. The overall form may be described as A, A1, B, B1, A, Coda.

It is recognizable as a waltz albeit in a version that Steve Wozniak might have performed on Dancing with the Stars since it requires 1 2/3 feet! Instead of the usual 3/4 time signature it is in 5/4 and is usually divided into 2+3 beats. This outraged many critics at the time but it is now quite delightful.

Example 3. Second movement. Woz’s waltz

The third movement is a brilliant march that seems to cast aside the despair of the first movement. It can also be seen as being ironic; a desperate bid for happiness which confirms its futility.

Example 4. Third movement March

True to his initial plan described the letter to his nephew Bob, the symphony does not end with the usual per aspera ad astra triumphal finish. Instead it is as Balanchine described it, “Everything stops, as if a man is going into the grave.” The theme is interestingly scored or cross-voiced between the first and second violins. In the example I unwound the theme as it is perceived.

The andante second theme is more flowing which builds to a climax to be followed by a greater climax based on the first theme. After it dies away we hear the trombones and tuba play a chorale.

The second theme goes down, down and finally dies out as the symphony began; softly, slowly, in the nether regions of the strings.

Examining the final – or near final – works of composers from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries we tend to seek a sublime summation of the artist’s work. Failing that, we tend to embellish them and his final circumstances with anything from small exaggerations to full blown myths. But as we’ve heard today, these works stand on their own without them.

Resources

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=0195170679][amazon template=iframe image&asin=3795766834][amazon template=iframe image&asin=0486299546][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B0018M6J5Y][amazon template=iframe image&asin=019816596X]