Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Born March 25, 1881 in Nagyszentmiklós Hungary (now Romania).

Died September 26, 1945 in New York City.

Concerto for Piano No. 3, Sz. 119

Composed in the summer of 1945.

First Performance: February 8, 1946, in Philadelphia, with György Sándor as soloist, and Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes,, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, and strings.

Neglected in his homeland, Bartók left war torn Europe and arrived in the United States in October 1940 only to be classified the following year as an “Enemy Alien.” During his final years he trudged his way via the NY subway to work with the folk music archives at Columbia University. His final compositions were compromises for the taste of the free market in order to cover his living expenses. As his illness intensified he was all but forgotten and died in poverty. Not even a 20th century composer of sometimes “difficult” music can escape romantic myths after his death.

Bartók’s final years were grim but not as horrible as described by propagandists. In 1943 when he became seriously ill, his medical bills and long term care were paid by Harvard University and later the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). Many of his friends including Ormandy, Reiner, Szigeti and Benny Goodman campaigned on his behalf for financial support. In May 1943, he was visited in his hospital room by the conductor Serge Koussevitzky who commissioned him for what became the very popular Concerto for Orchestra.

His income then became more secure. While Bartók did not have the coin afforded to even the worst modern professional athlete he was not destitute. He and his second wife, pianist Ditta Pásztory Bartók, had hoped that they would have frequent and lucrative concert opportunities in the United States but they failed to materialize.

He was offered teaching positions by several leading American conservatories but turned each of them down. One of his main reasons for the move to the US was to continue his ethnomusicological work. To the end he was occupied with the folk music of many different countries. He successfully completed several projects before his death.

The Piano Concerto No. 3 was written in secret as a present for his wife Ditta. He had hoped that it would be a vehicle that would provide her with some income after his death. He worked on this concerto and the Viola Concerto at the same time which was not his usual habit. Since it was for his wife he devoted more time to this concerto and came very close to finishing it before he had to go to the hospital for the final time. The final seventeen measures were written in his short hand. These measures were completed by his friend the composer Tibor Serly. A few more tempo and expression markings were added by others.

The style of this concerto is quite different from the preceding two. The scoring is more transparent and the soloist’s part is less percussive – which fitted Bartók’s piano playing but not that of his wife.

There are three movements.

I Allegretto

II Adagio religioso

III Allegro vivace

The Allegretto first movement is cast in a fairly straightforward sonata form. The soloist enters playing the main theme which has a decidedly folk like flavor with one note in each hand, two octaves apart, over rustling strings. The second playfully scherzando theme features a falling third motif that reappears throughout the movement.

The movement ends with an interchange between the piano and the woodwinds taking turns with the falling thirds motif, with the piano having the last word.

Example 1. First movement

The Andante religioso (he never used the word religioso anywhere else) second movement begins with a soft flowing theme with the strings entering canonically.

Example 2. Second movement

When the strings fade away the piano enters quietly playing a chorale like passage unaccompanied. In this first section the soloist alternates unaccompanied passages with the strings. This recalls Beethoven’s “Heiliger Dankgesang” (Holy song of thanksgiving by a Convalescent), the third movement of the String Quartet, op. 132, written after Beethoven recovered from an illness. The first section ends with the horn softly intoning a single E. The middle section is his “night music” (similar to his 1926 Out of Doors suite) where we hear like bird calls tossed between the piano, oboe, clarinet and flute. Like Messiaen, these were actual bird calls notated by Bartók the previous year when he was recuperating on a trip to Asheville, North Carolina. The material from the first section returns in the woodwinds, while at the same time the soloist plays a Bach like two-part invention with pianistic flourishes at the ends of phrases. A climax is reached in the coda which begins with the strings playing the chorale forte. The soloist plays a declamatory sequence but is followed by the strings softly playing the chorale to end the movement.

The Allegro vivace third movement follows without a break.

It is a rondo with two fugal episodes and a coda.

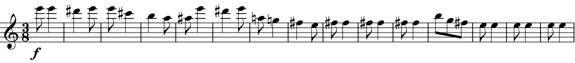

Example 3. Third Movement

Following the last measure, Bartók had written the Hungarian word, vége, meaning “end.” Unfortunately it was also the end for him.

Ditta did not play the premiere of the concerto after Bartók’s death. Instead it was another of his pupils, György Sándor who was the soloist for the premiere. Ditta moved back to Hungary and eventually played the concerto decades later.

Resources

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00000C2J8][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000TPYXM2][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000001GJ7][amazon template=iframe image&asin=B000VUVGH0]

Score:

[amazon template=iframe image&asin=B00385RJEE]